A couple of years ago, I watched an interview of Sir David Attenborough, a world renown naturalist whose work has spanned over 60 years. I was fascinated by his schoolboy memory of plastic being heralded as a wondrous new invention.

Of course, within the course of a few minutes, he delved into the reality of our times - living with plastic. The devastating effects are well-documented and continue to be monitored around the world.

Sir David Attenborough: Plastic Then and Now

While these massive oceanic dump sites have been growing, there is some good news. A recent article by Eileen Shim in PolicyMic titled Harvard Scientists May Have Just Solved One of the Biggest Environmental Issues of Our Time had me seeing a light at the end of the tunnel.

Shrilk: Developed by Harvard Scientists

Javier G. Fernandez and Donald Ingber

The Shrimp Part

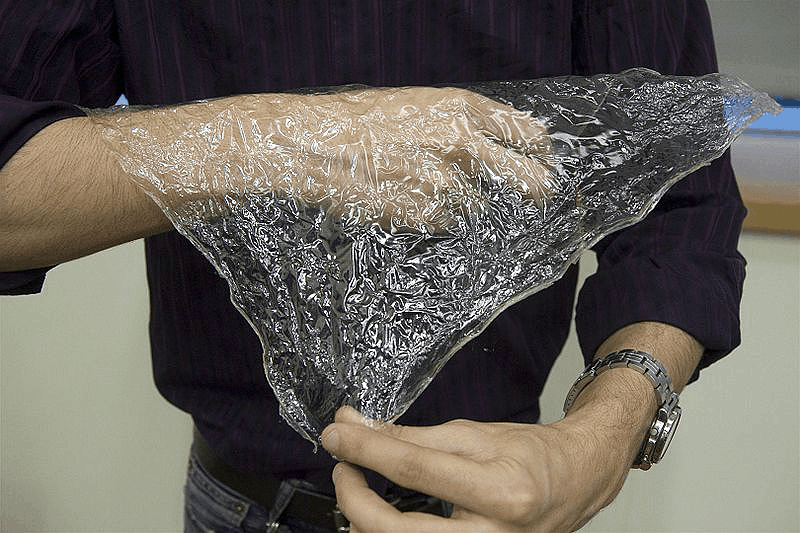

Shrilk was developed a few years ago, in 2011. It's made of discarded shrimp shells and silk protein (hence the name was a combination of the words shrimp and silk).

The fascinating property of shrilk is that it's light yet extremely strong. Its design brilliantly  U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration / Public Domainmimics insect cuticle and results in a clear, thin, flexible material as strong as aluminum. By varying the water content, scientists can create a wide range of shrilk pliability (from rigid to flexible).

U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration / Public Domainmimics insect cuticle and results in a clear, thin, flexible material as strong as aluminum. By varying the water content, scientists can create a wide range of shrilk pliability (from rigid to flexible).

And - get this - it's 100% biodegradable. In fact, it's good for the environment.

Discarded shrimp shells are treated with the alkali sodium hydroxide to create chitosan. Chitosan has numerous applications, biopesticide being one of them. Not only does it help plants fight off fungal infections, it helps with photosynthesis, enhances growth and vigor, and increases sprouting and germination.

What's more, chitosan is one of the most abundant (and affordable) biodegradable materials in the world. When discarded, items made of chitosan degrade in just a few weeks - which releases nitrogen and supports plant growth.

Chitin and chitosan have the same chemical structure. Chitosan is used commercially and is made by the deacetylation of chitin (a process which removes one or more acetyl groups from the molecule). Primarily, sodium hydroxide and water are all that is required to produce chitosan from chitin.

What if there isn't enough shrimp? Copepods are abundant tiny crustaceans which can provide another source of chitin. They are believed to produce billions of tons of chitin per year.

The Silk Part

Krish Dulal (Wikipedia) / Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 GenericThe silk protein component of shrilk is fibroin which comes from the domestic silkworm.

Krish Dulal (Wikipedia) / Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 GenericThe silk protein component of shrilk is fibroin which comes from the domestic silkworm.

I was amazed to learn that the process of combining chitin (from shrimp shells) and fibroin isn't chemical at all.

In the December 2010 issue of the International Journal of Environmental Science and Development (Vol.1, No.5), I sourced out a paper by M. K. Sah and K. Pramanik titled Regenerated Silk Fibroin from B. mori Silk Cocoon for Tissue Engineering Applications. In it, I learned that silk fibroin fibers are a unique protein which is spun by the silkworm (Bombyx mori).

Shrilk is made by layering these biodegradable materials into a matrix which undergoes only two stages: dehydration and molecular arrangement.

How will it be made waterproof? I'm wondering that too. I suspect that either a plant wax or beeswax coating would need to be added to some shrilk products. (I know declining bee populations are of great concern in many areas of the world).

Up next is a 59 second video from Harvard's Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering. It shows a California Blackeye pea plant sprouting from a chitosan bioplastic-based soil.

Pea Plant Sprouts in Chitosan Bioplastic Soil

What About All the Plastic Waste We've Left Behind?

Bui Linh Ngan (linh.ngan on flickr) / Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 GenericOkay, so once shrilk becomes mass produced to replace petroleum-based plastics, how do we clean up the massive amounts of discarded plastic in the oceans and on the world's beaches?

Bui Linh Ngan (linh.ngan on flickr) / Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 GenericOkay, so once shrilk becomes mass produced to replace petroleum-based plastics, how do we clean up the massive amounts of discarded plastic in the oceans and on the world's beaches?

Make it a commodity - something of value.

There's one such organization doing just that called The Plastic Bank. Its founder, David Katz, envisioned plastic as a type of currency. In fact, May 2014 marks the official launch of the first Plastic Bank located in South America.

Many of the poorest people in the world will be given a real chance to thrive economically.

Up next is an inspiring news report by Tess van Straaten about the two Canadian entrepreneurs from Victoria, BC who had the vision and drive to make The Plastic Bank a reality.

Reducing Waste Plastic & Poverty

A Challenge That Can Be Overcome

Almost 300 million tons of new plastic is made in the world every year. Yet only 10% of the world's plastic is recycled.

Is there a business out there than can recycle every type of plastic? Yes, The Plastic Bank has teamed up with Dr. Mike Biddle, founder of MBA Polymers, Inc. "The first company in the world that can take any mixed plastic and separate it," says David Katz, President and founder of The Plastic Bank.

But there are thousands of manufacturing companies producing petroleum-based plastics in the world. I feel we need to (as a society) continue to make it taboo to buy petroleum-based plastics. We need to demand that recycled ocean plastic is what we want and are willing to pay for.

What it may take:

1) Financial assistance for petroleum-based plastic factories to convert their facility to produce recycled ocean plastic.

2) An acceptable (and doable) timeline for businesses to adhere to new standards set out by regulatory bodies.

3) Laws and/or fines imposed on businesses who violate new guidelines and continue to manufacture petroleum-based products.

Still skeptical? When I was a teenager, students (and teachers) would go for a smoke break on the school's patio. Even though I didn't smoke, I was offered cigarettes. And I was teased a bit for refusing to smoke.

Today, many of those same students wished they'd never started smoking. Some have quit, some have lung cancer, and some still smoke. Not everyone quit smoking and cigarettes aren't outlawed, but in 25 years attitudes and habits have changed a great deal.

My point is this: Educating society and getting people to care about the environment works. Those companies willing to recycle ocean plastic need to be the ones we reward with our purchases.

Why Consumers Want and Need Products

made of biodegradable plastic or recycled ocean plastic